Michigan chestnut crop report

The Chestnut crop report from Michigan State University Extension for the week of May 9, 2023, and written Erin Lizotte, addressed weather, management activities, fertility, insects and disease.

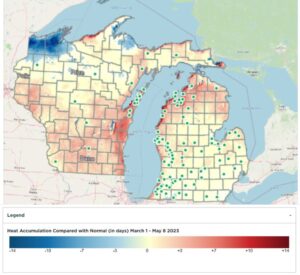

Weekly weather review

Much of the state of Michigan remains almost dead on for the 29-year-average for heat accumulation. Cumulative heat and degree days are not great illustrators of the somewhat large swings in conditions this spring. The large swings in conditions can lead to a lack of predictability in plant and pest development.

Management activities

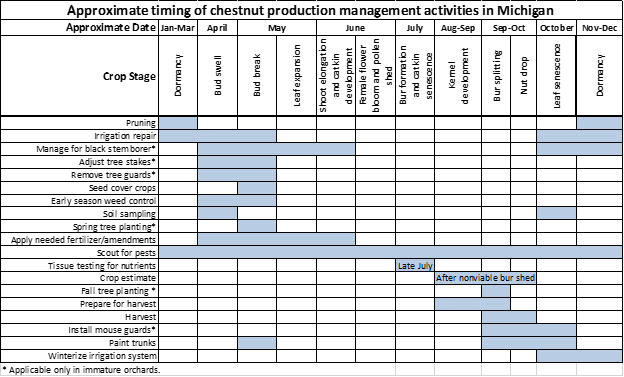

Chestnuts in southern Michigan are leafing out. Chestnuts further north and in cold locations may still be in bud swell. It is a busy time of the year for orchard activities. Growers may be soil testing, getting the irrigation up and running, planning spring fertilizer applications as needed, removing mouse guards and scouting for pests. This is also a great time of year to paint trunks to reduce southwest disease.

Fertility

Most growers using granular fertilizers are planning to apply them soon. As a reminder, for nutrient management considerations, please reference the 2023 Michigan Chestnut Management Guide from Michigan State University Extension (MSU Extension) or the Nutrient Management section of the MSU Extension Chestnut website.

Insects

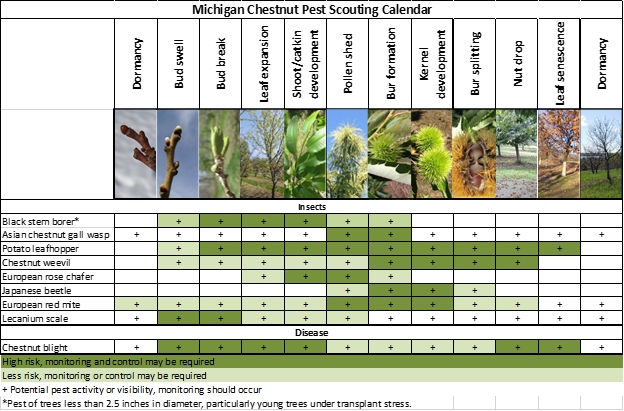

Black stem borer

Growers are reporting the first black stem borer adults in traps in west central Michigan and spraying trunks to protect young trees. Black stem borer will infest and damage a wide variety of woody plant species, including chestnuts. Black stem borers are attracted to small trees with less than a 4-inch trunk diameter and stressed trees that produce ethanol. Female borers create tunnels in trunks to lay their eggs. These tunnels damage the tree’s ability to translocate water and nutrients.

Overwintering adults become active in late April or early May after one or two consecutive days of 68 degrees Fahrenheit or higher, often coinciding with blooming forsythia. Adult black stem borers are very small (0.08 inches long).

Growers are encouraged to use a simple ethanol baited trap to monitor for activity starting in mid-April. Traps are most effectively deployed near adjacent wooded areas at a height of 1.6 feet. Hand sanitizer is an easy and accessible bait but should be refreshed every few days.

Growers with small, vulnerable trees and positive trap catches or a history of damage will need to apply a trunk spray to prevent damage. The time to spray an insecticide for this pest is when females are flying in the spring before colonizing new trees. Young trees near the perimeter of orchards, especially near woodlots, are at greatest risk of injury. Because they are so tiny, it is impossible to visually monitor for adults to determine the optimum time to apply an insecticide, so trapping as described above is recommended to detect adult activity and apply treatment.

Pyrethroid insecticides applied as trunk sprays have shown the most promise in reducing the number of new infestations within a season. For a list of registered pyrethroids for use in Michigan chestnuts, refer to the Michigan Chestnut Management Guide.

Later in the season, remove and burn any damaged dead or dying trees. It is also important to make sure all large prunings and brush piles are either burned, or chipped and composted as they may harbor overwintering adults and contribute to future infestations.

European red mite

In 2022, some growers reported higher than typical European red mite populations. European red mites overwinter as eggs in bark crevices and bud scales and are the most commonly observed species in Michigan chestnut orchards. Eggs are small spheres, about the size of the head of a pin with a single stipe or hair that protrudes from the top (this is not always visible). Eggs can be viewed with a hand lens or the naked eye once you have established what you are looking for.

Growers can scout for overwintering eggs and early nymph activity in the spring to assess population levels in the coming season. As temperatures warm, overwintering eggs hatch and nymphs move onto the emerging leaves and start feeding. Adult European red mite are red in color and have hairs that give them a spikey appearance. Adult and nymph feeding occurs primarily on the upper surface of the leaves. This first generation is the slowest of the season and typically takes a full three weeks to develop and reproduce. This slow development is due to the direct link between temperature and mite development. Summer generations, favored by the hot and dry weather, can complete their lifecycles much faster with as little as 10 days between generations under ideal conditions.

As you scout, remember that not all mites are bad. Consider documenting the levels of predacious mites in your orchard. If healthy populations of mite predators exist, they will continue to feed on plant parasitic eggs and nymphs and can be an effective component of your mite management program. Predaceous mites are smaller than adult European red mite and two spotted spider mite, but they can be seen with a hand lens and typically move very quickly across leaf surfaces.

Disease

Existing chestnut blight infections (caused by Cryphonectria parasitica) can be observed. There are no commercially available treatments for chestnut blight. Growers may prune out infected branches or cull whole trees as needed to limit disease pressure. Infested material should be burned or buried to further limit inoculum spread. To learn more about chestnut blight, visit the pest management section of the chestnut webpage.

For more information, visit extension.msu.edu.

This article was originally published by Michigan State University. The entire Michigan chestnut crop report from Michigan State University Extension is available by clicking here.

This work is supported by the Crop Protection and Pest Management Program [grant no 2021-70006-35450] from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the USDA.