Dec 15, 2021Merced County ranch hopes to keep farmland in the family

In 1909, long before cities were formed, third generation farmer, Randy Fiorini’s grandparents Francis and Mable made the life-changing move from Southern California to our most fertile soil, the Central Valley, putting roots down in Merced County, between what is now Turlock and Delhi.

To say they started with nothing is an understatement. Like many settlers, the Fiorini’s farm began with a small herd of dairy cows on a piece of dry-farmed land.

“If it hadn’t been for his wife, Mabel, Francis wouldn’t have known how to hook up the horses to the plow,” Randy said jokingly about his grandfather.

Today, Fiorini Ranch is farmed and managed by Randy and the fourth generations of Fiorinis; his children Jay Fiorini and Stacy Parker. With over 100 years of farming history, the ranch has endured vast changes. In 1922, the original 360-acre homestead was divided among the two boys of the family. With his portion, Randy’s father diversified into winegrapes and stone fruit orchards, which they farmed for several years before eventually phasing out into solely almond, walnut and peach orchards.

Given the family’s deep farming history, Randy naturally followed in the footsteps of the generations before him. He recalled starting to work hand-in-hand with his father at age 10, and like many farm kids, completed some of the least desirable farm tasks, such as rubber mallets to knock the nuts off the trees. Randy remembered a conversation with his father who expressed, “Unless you do all these jobs, you’ll never be a good farmer.”

Randy attended Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo, receiving a bachelor’s degree in fruit science. Before he graduated, he bought his first 60-acre farm next door to the family’s original homestead ranch. At the time, some friends and family questioned his judgment because the ground had been stripped of topsoil.

“Most people around here didn’t think it was farmable,” Randy said. “The price was so cheap. I went to the Farmers Home Administration and they gave me a start-up loan. That’s really the piece of property I got started on in 1973. Needless to say, we’re almost 48 years into it and it’s become very productive farmland.”

The transformation didn’t happen overnight and reiterated Randy’s long-term commitment to the land. Healthy soil-building practices, such as compost and manure applications, as well as water-use efficiency technologies like micro-sprinklers are all utilized. The land is now in its third planting of almonds. Randy said this 60-acre property is near to his heart because it is adjacent to the ground where his grandparents started their farming journey and is the first ground he ever owned.

After graduating from college, Randy returned to the family operation, took over all farm management decisions, and by large, grew the nut side of the business. The ranch collectively grew to over 700 acres, and today they farm more than 500 acres of almonds and approximately 100 acres of walnuts and peaches.

Taking a stand

More recently, generational farming is a topic that has been extensively discussed among the Fiorinis. In recent years, Randy has witnessed encroachment by urban development, record-breaking land prices, and increased production costs – all factors that just don’t pencil out for the farmer. The lure of development is near and threatening, and with Fiorini Ranch’s close proximity to major highways and towns, the farm’s potential to be paved over is daunting.

Two of Randy’s neighbors with farms also in the path to be developed, acted against this threat, and placed their farmland under agricultural conservation easements (ACE) with California Farmland Trust (CFT).

The easement consists of a legal transaction between the landowner and land trust, where the landowner voluntarily sells or donates the development rights of their property to the land trust. The farm continues to be owned and operated by the owner, while simultaneously being forever protected.

“I inquired with my neighbors about the experience, and they were all very favorable and felt like it was one of the best decisions they’ve ever made,” Randy said. After sitting on the idea, he proposed the possibility of an ACE to his children, to which they responded with great eagerness.

“Growing up here and being surrounded by family history, it’s important for us to have this land for future generations,” Stacy said. Jay added, “I want to preserve this core farmland that exists and hope it can provide opportunities for our kids and even their kids.”

Nearby development threats

Starting with the protection of the 60-acre property with an agriculture conservation easement (ACE), will not only ensure the farm remains in agriculture, but Randy said he hoped to send a message to area developers and encourage other nearby landowners to follow suit.

“The threat is from Delhi,” he said. “In most valley communities, they grow up around (Highway) 99. Delhi has been growing to the west, and land development opportunities that exist now to the east, I think, are more attractive to land developers. So, 160 acres adjacent to Delhi that we’re located next to are likely to be the first to go. And the landowner is eager to sell.”

“We’re right on the edge of the Delhi sphere of influence. I think we want to signal to Merced County planning department, that they should not think about residential housing development beyond this line that we’re trying to form,” Randy added.

Charlotte Mitchell, executive director at CFT agreed, adding the Fiorini project complements the more than 11,000 acres that CFT has already permanently protected in Merced County. “Some of the most productive farmland located in Merced County is also under threat for urban development,” she said. “It’s important we strategically invest in protecting sustainable farmland that provides food and benefits the environment.”

“With urbanization creeping closer, land prices have skyrocketed to the point that purchasing a piece to farm doesn’t pencil out,” Fiorini said. “Potential buyers are either willing to shell out for 3- to 4-acre ranchettes or they are developers who plan to split the property for housing. The high prices also prove enticing to farmers looking to retire.”

Protect Fiorini Ranch campaign

Currently, the Fiorinis are pursuing an agricultural conservation easement with California Farmland Trust on the 60-acre almond orchard that Randy first purchased. When applying for ACE grant funding, raising match funds is becoming a common requirement, Randy explained.

An application was submitted to the Sustainable Agricultural Lands Conservation Program (SALC), a collaborative grant funding program between the California Department of Conservation (DOC) and the California Strategic Growth Council (SGC). The program will fund 75% of the cost needed for the Fiorinis’ easement. CFT was successfully awarded grant funding in November of 2021 and are now working on securing the remaining funds.

The remaining 25%, approximately $165,000, must be provided by other sources. To fulfill the 25%, CFT pursued a match funding grant with the Henry Mayo Newhall Foundation, which has a long history of supporting communities and agriculture throughout California.

“When we found out that they would consider funding an agricultural conservation easement, we prepared a presentation for their board,” Randy said. “They liked what we were trying to do and pledged to provide match funding.”

The Newhalls agreed to provide up to $80,000 to fund the Fiorinis easement, leaving it up to Randy, his family, and CFT to find the remaining funds. Over two years, the Protect Fiorini Ranch campaign is being conducted by CFT to raise $85,000 for the Fiorinis easement project. With nearly half the funds already raised, come the end of 2022, CFT must raise the remaining $45,000.

Being part of the solution

While the primary purpose of these funds will be dedicated to protecting Fiorini Ranch, the Fiorinis articulated the bigger picture to be far more valuable.

“The single biggest need in California is to create an awareness about the importance of agriculture,” Randy said. “We’re in a position to draw a line and become the buffer between urbanization and agriculture. You don’t have to go more than about 80 miles west and see what’s happened to the Santa Clara Valley. It could happen here, and that would be a shame.”

If completed, Fiorini Ranch will be the 27th ACE within a 10-mile radius of their farm. The Fiorinis hope this buffer will stimulate conversation with policymakers resulting in more funding, and they hope to increase landowner dialogue to take action in protecting their own farms.

“Our neighbors influenced us to move in this direction, and we will likely influence others,” Randy said. “If we’re going to preserve agriculture in California, the Central Valley is the last stand. If this falls, then kiss California agriculture goodbye.”

To learn more about this project, visit www.cafarmtrust.org/protect-fiorini-ranch.

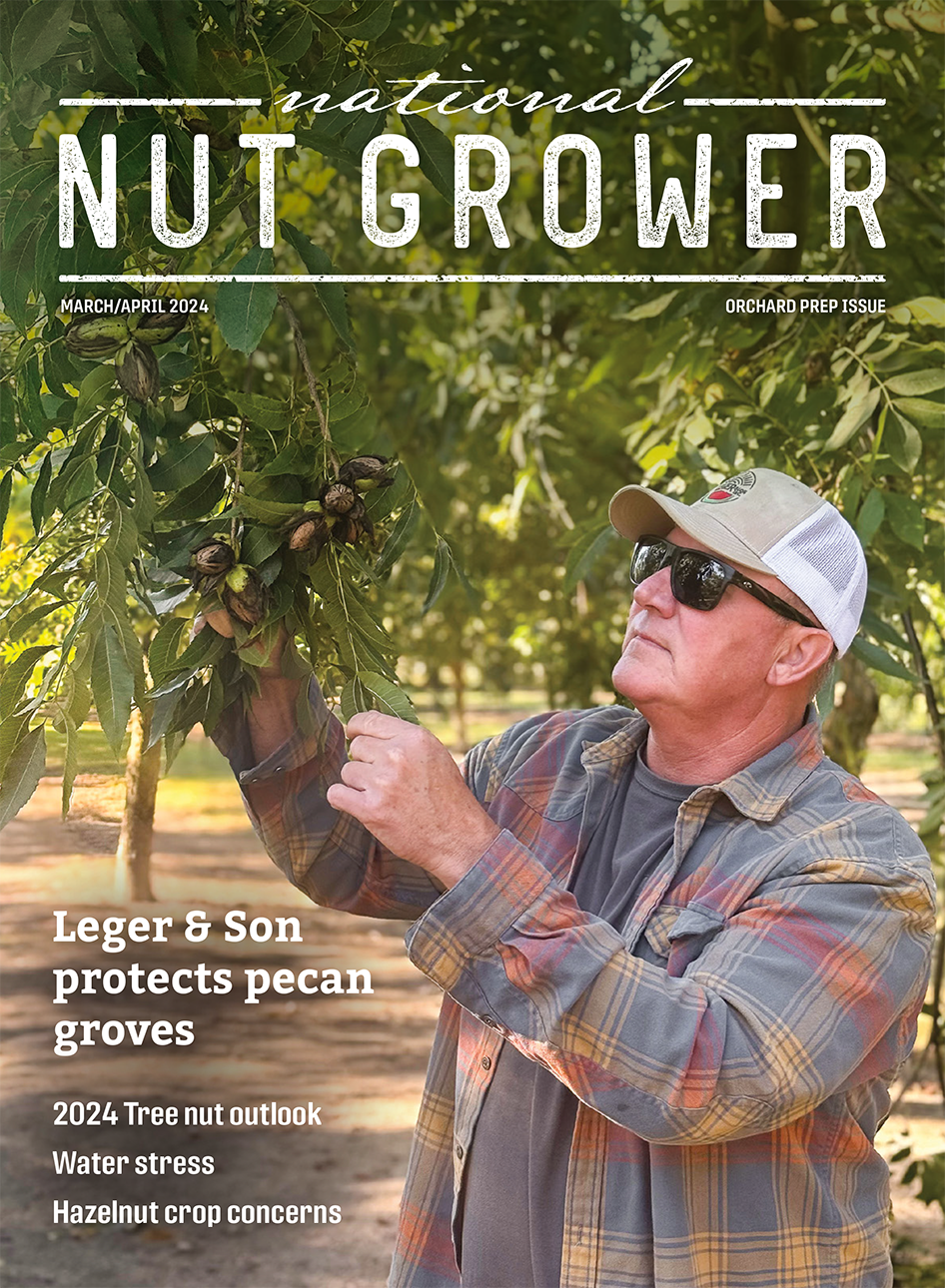

Photo at top: Randy Fiorini.