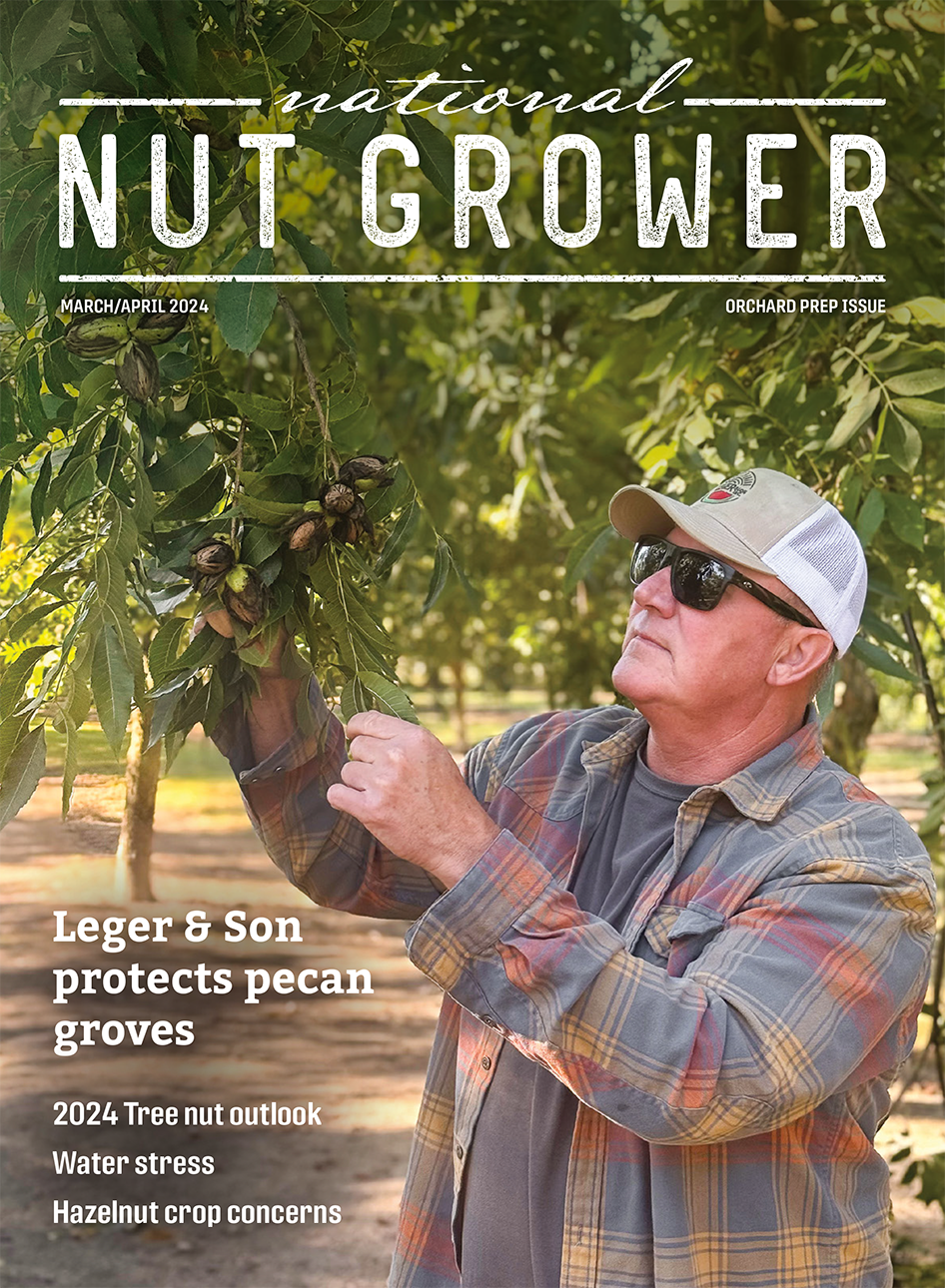

Nov/Dec 2022

Pruning young pecan

A significant increase in pecan acreage in Georgia means lots of new trees. The dormant season is here, but the activities in the field don’t stop. For pecan, it may be a grower’s last chance to plant a winter cover crop, it’s the ideal time to take soil samples, and an important time to prune new pecan trees.

Pruning sets the stage and guides the structure that will be required to carry heavy crop loads and withstand shakers and extreme weather. It’s within these first four years that it’s important to prune trees to reset the tree structure, otherwise it becomes too difficult.

“The first-, second-, third-, and fourth-year pruning is all focused around a central leader” said Andrew Sawyer, area pecan agent, University of Georgia (UGA) Extension. “And when new trees are planted, we cut them in half to alleviate transplant stress, which allows the tree to survive.”

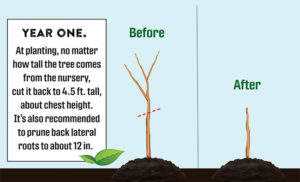

Year One

The first-year pruning of the tree doesn’t specifically focus on the tree’s structure, but rather removes tree structure all together. What it is designed to do, however, is have the tree focus on developing a more extensive root system during the early years instead of the canopy.

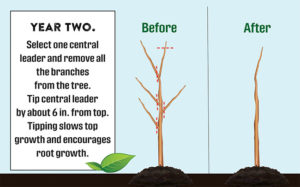

In second year pruning, UGA recommends cutting off all branches except for one big, main branch that will become the central leader, and then tip the main branch by a few inches.

Year Two

“Tipping doesn’t have anything to do with the height of the tree,” said Sawyer. “It’s done to make the tree grow more branches next year, by slowing down the growth of the top part of the tree.”

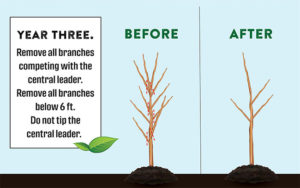

The third year is similar to the second, where crow’s feet and every branch below 6 ft. is removed.

Year Three

When the tops of the tree are cut, they often grow back with what are colloquially called “crow’s feet,” where 3-4 branches grow out of a single point in that second year of pruning, creating a tangled mess in the treetops.

At fourth leaf, there shouldn’t be any lower branches that need pruning, as this was done in the year prior. In the fourth year, crow’s feet should be removed, as well as any branches that compete with the central leader.

“Sometimes, there will be a few Vs. You don’t want any of that because a straight line wind will come through the top, and it will split the bark down the whole length of the tree,” said Sawyer. “It’ll rip the bark all the way down the trunk and ruin the tree.”

When the trees fork or have narrow crotches and are not pruned, the tree can grow into a large V shape that lacks strength because the limbs are so close together and can push against one another.

“It becomes a chainsaw situation, and you’re just trying to salvage the tree, but you’ve got to cut half the tree off to get rid of the fork,” said Sawyer.

Branches are strongest when they’re close to a 90-degree angle straight out from the trunk, because what connects that branch to the tree is wood, said Sawyer. But branches at a 45-degree angle or less are getting their strength from the bark, which actually has no structural support.

If trees in the third and fourth years have any branches that are growing closely with the trunk — or straight

up alongside it — it’s best to remove them, because the tighter the branches are with the trunk, the less strength they will have. And those, Sawyer said, are the ones that the wind will split.

Some growers who opted to skip pruning in those early years have experienced tree loss due to wind. The tree grows quickly, and by year six or seven, any pruning done will require a chainsaw. It’s a lot of work those first four years, said Sawyer, and something a grower won’t see the fruits of until later.

“People think that when they prune a tree that they’re hurting it, but the trees love it,” said Sawyer.

UGA research has shown that pecan trees don’t put on a lot of significant branches in the first four years while they’re putting on roots. This is also why certain fertilizer

rates are so important for young trees. Too much nitrogen in the early years can cause too much canopy growth, which can then cause a tree to fall over since it never developed the proper root structure to support itself. It outgrows its own root structure, which can be detrimental in extreme weather, like hurricanes.

In 2018, Hurricane Michael hit Southwest Georgia, destroying many pecan orchards, and so much so that Georgia lost its No.1 spot as U.S. pecan producer. (It has since been reclaimed.) Sawyer saw firsthand how growers lost trees.

“Sometimes growers apply a lot of fertilizer and water, and then the trees grow really quickly. And the trees need water, but they also need to grow roots. There’s a certain amount of stress they can be under that makes them grow deep roots,” said Sawyer.

One grower near Sawyer lost over 30% of his orchard — about 1,000 trees — during Hurricane Michael.

Lenny Wells, professor and pecan Extension specialist, UGA, conducted additional research after Hurricane Michael to determine the differences between hedged and unhedged pecan orchards. Hedging is still fairly new to Georgia pecans, but quickly gaining traction in a move to become the new cultural practice, and for good reason.

“The hedged trees survived better by about 60%,” said Sawyer. “It was a huge difference.”