Jul 6, 2021Michigan chestnut crop report for the week of June 28, 2021

Pollen shed is underway in most locations. Japanese beetle emergence begun in southern Michigan. The window for lecanium scale crawler management is approaching.

Weather

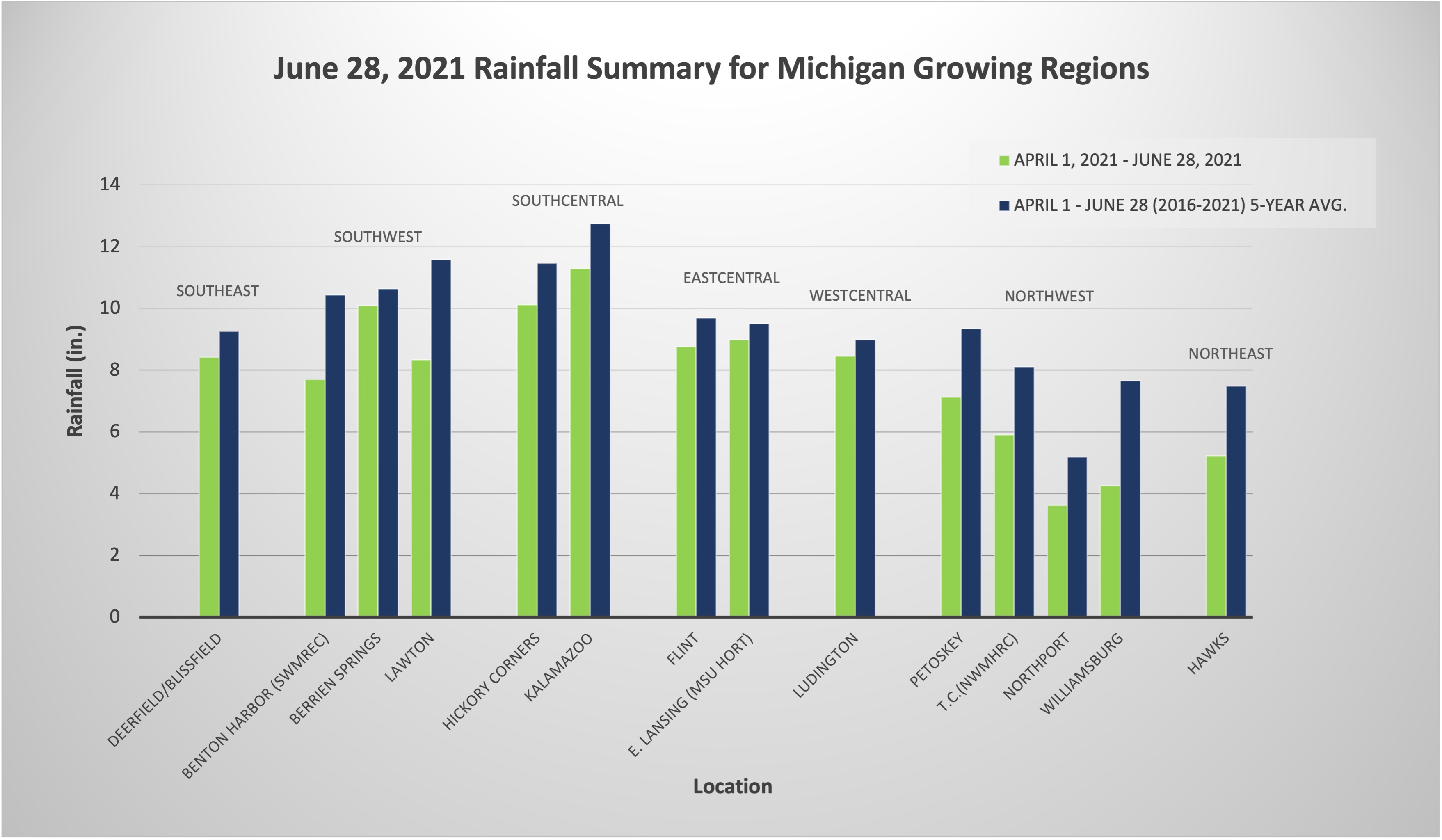

Some areas of the state experienced severe weather over the weekend with very heavy precipitation. The southern two-thirds of lower Michigan received at least 2 inches of rain; certain areas received over 5 inches, which caused localized flooding. In only two weeks, water deficits have nearly disappeared across most of the state. In northern lower Michigan and especially the northeastern Lower Peninsula, rainfall was only scattered and some moisture deficits remain. Although, because of heavy precipitation across most of the state, there has been a 25% increase in soil moisture in top 3 feet of soil profile.

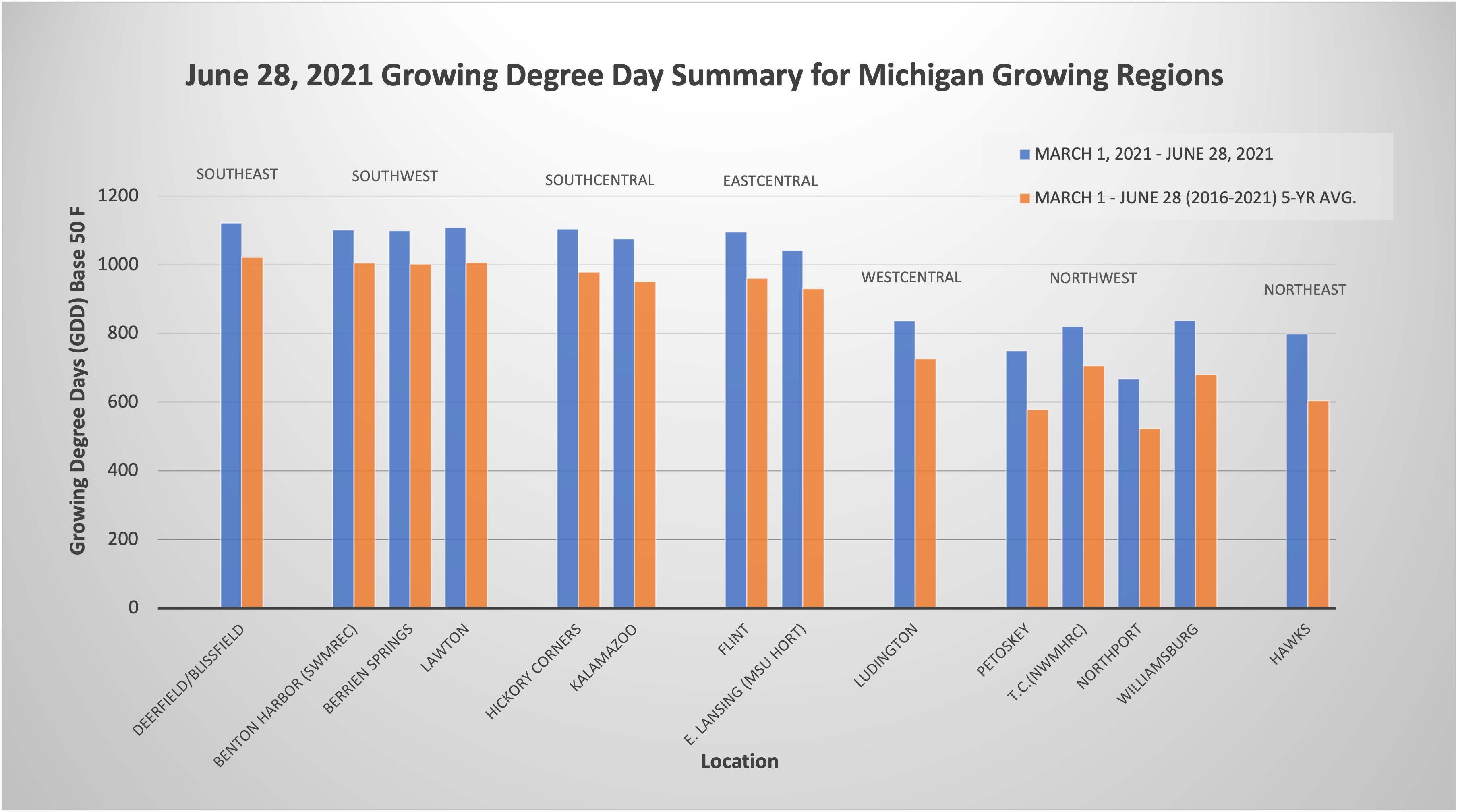

Temperatures were 2-4 degrees Fahrenheit lower over the last few days. We are still generally ahead in growing degree days (GDD). Chances are likely for additional precipitation through Wednesday and then isolated showers Thursday. A cooler, dryer pattern will take shape as we move into the holiday weekend, and then by early next week temperatures will increase to above average.

Both the 6-10 day forecast and 3-4 week outlook suggest warmer than normal temperatures, although not nearly as warm as the all-time record breaking heat smothering the Pacific Northwest at this time.

Watch the most recent agricultural weather forecast from Michigan State University state climatologist Jeff Andresen.

Crop development

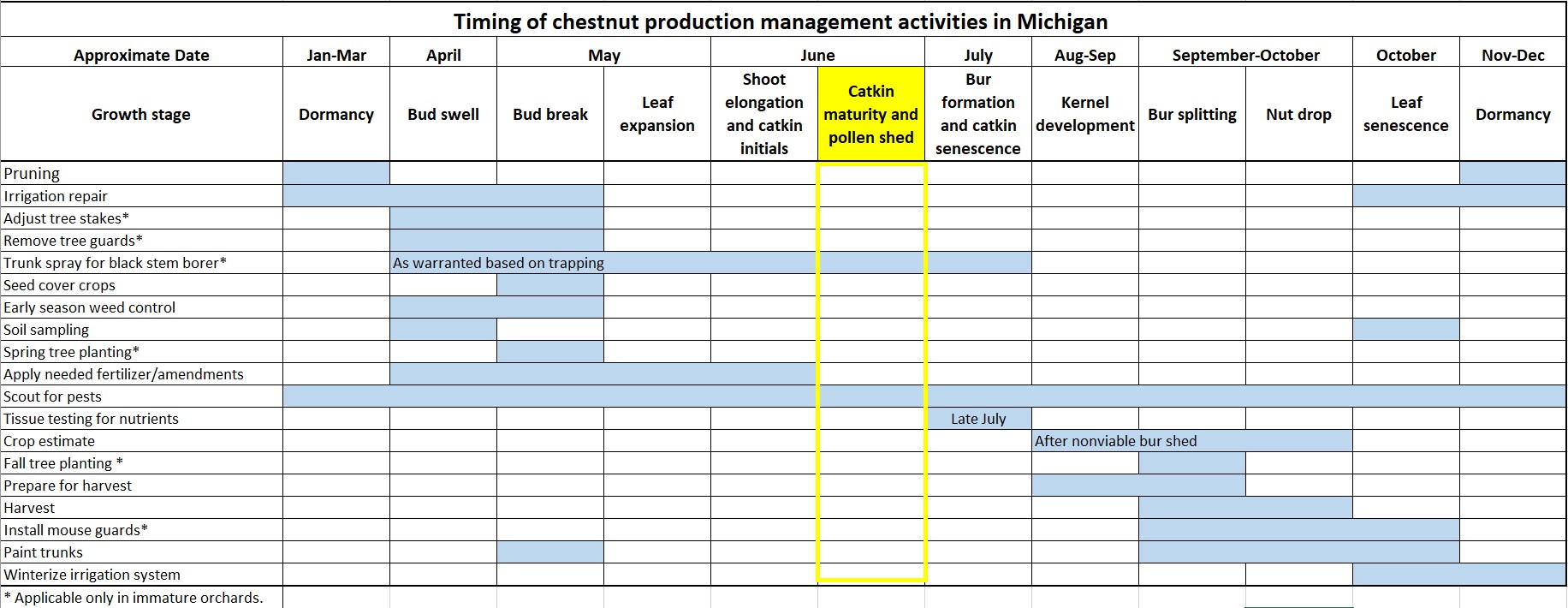

Pollen shed is underway to varying degrees across the state. The window for nitrogen applications is closing.

Northwest Michigan

Pollen shed has started in observed cultivars. European rose chafer numbers are building and young trees with limited leaf area may need to be protected. Potato leafhopper need to be managed.

West central Michigan

Observed cultivars have mature catkins. Pollen shed has begun.

Southern Michigan

Pollen shed is underway. Asian chestnut gall wasp emergence has begun. Potato leafhopper pressure continues. Japanese beetle emergence has begun.

Fertility

Growers wanting to do a leaf tissue test this year should be sampling now. Sampling chestnut leaf tissue for analysis is similar to protocol in other crops, with a couple important caveats.

- Samples should be collected from this year’s new growth before vegetative terminal growth stops for the year. Terminal growth typically stops in early August as the trees start developing burs. Samples taken after terminal growth stops will not be accurate.

- Collect five to 10 leaves per tree from multiple terminal branches. Be sure to sample along the length of the new growth and do not just select the outermost leaves.

- Be sure to carefully read and follow the protocol from the testing facility you plan to utilize to ensure you receive a valid report.

There are many labs that provide leaf analysis testing, a few are listed here for your convenience.

For more information on the general protocol for nutrient sampling, refer to the MSU Extension article, “Time to collect leaf samples for nutrient analysis.”

MSU would love to receive a copy of your tissue test results! Please send them to Mario Mandujano at mandujan@msu.edu.

As a reminder, for nutrient management considerations, please reference pages 5-7 of the 2021 Michigan Chestnut Management Guide or the Nutrient Management section of the MSU Extension Chestnuts website.

Integrated pest management

Growers should be scouting orchards weekly to identify emerging issues. At this time, growers can actively scout for many pests, but the most recent to arrive include Japanese beetle and potentially chestnut weevil. The window for treating lecanium scale at crawler stage is also approaching and should be carefully monitored by growers experiencing this issue.

Insects

Asian chestnut gall wasp presence has been confirmed in southwest Michigan and adult emergence was confirmed this week. Gall wasp adults are very small, about 1/8 inch (3 millimeters) long and have black bodies with yellow legs. Adult wasps lay eggs inside chestnut buds over a four to six week period, typically extending from the last week of June to the second week of August in southwest Michigan. This period corresponds to approximately 1,050 to 2,100 cumulative growing degree days (GDD), using a threshold temperature of 50 F (GDD 50) and a starting date of Jan. 1. Current degree day accumulation in southwest Michigan is 1,100 GDD 50. Eggs hatch after about 40 days, but the tiny larvae remain dormant in the buds throughout the winter until the following spring. Galls and infestations are undetectable until the following spring.

As leaves start expanding the following spring, the Asian chestnut gall wasp larvae begin to feed. Their feeding causes the plant to form small galls, 1/4 to 3/4 inch (5-20 millimeters) in diameter, on current-year shoots and leaves. Larvae feed and develop in chambers inside the galls for about four weeks and then pupate into adults. This new generation of adult wasps begins to emerge in late June, just as catkins begin to senesce. Adults continue to emerge and lay eggs for about six weeks.

While leaf galls usually have little impact, galls that form on current-year shoots can affect vigor and nut production of chestnut trees. Apical galls that form at the tip of shoots may be especially damaging. They reduce shoot elongation and can inhibit flower production, which reduces nut formation. Chestnut producers in Japan, Korea, several European countries and even some U.S. states, have reported yield reductions following Asian chestnut gall wasp invasion. Branch dieback has been observed in China, Japan, Korea, Italy and the U.S. when Asian chestnut gall wasp densities were high.

An array of methods to control Asian chestnut gall wasp have been employed by commercial chestnut growers, with varying levels of success. Integrating strategies for managing Asian chestnut gall wasp should prevent yield loss while minimizing unnecessary pest control costs and impacts on beneficial insects such as pollinators and natural enemies. Effective pest management starts with active scouting. Chestnut growers in western lower Michigan, particularly south of I-96 and west of Highway 127, should be scouting their trees for evidence of Asian chestnut gall wasp during the growing season and in fall or winter, after leaf drop.

If galls are abundant and nut production is low on heavily infested trees, growers may need to control Asian chestnut gall wasp adults with a cover spray of a broad spectrum, conventional insecticide. Generally, pesticide applications are not recommended because Asian chestnut gall wasp populations are adequately regulated by Torymus sinensis, a beneficial parasitic wasp.

The T. sinensis parasitoid and Asian chestnut gall wasp share a long co-evolutionary history in China and the life cycle of the parasitoid is well synchronized with Asian chestnut gall wasp. In early spring, as Asian chestnut gall wasp galls are forming, T. sinensis adult females lay an egg into a gall chamber where an Asian chestnut gall wasp larva is feeding. Each parasitoid larva feeds on an Asian chestnut gall wasp larva within the gall chamber throughout the summer, eventually killing the Asian chestnut gall wasp larva. Parasitoid larvae remain inside the galls throughout the winter. As chestnut buds break and new galls form in spring, adult parasitoid wasps emerge from the dry, previous-year galls to oviposit within the green, succulent, current-year galls.

Fortunately, the T. sinensis parasitoid seems to have arrived in southwest Michigan at about the same time as Asian chestnut gall wasp and this beneficial wasp appears to be spreading. Old galls should not be removed as the beneficial parasitoids may still be developing inside the old galls. Removing those galls will have no effect on Asian chestnut gall wasp density but could reduce the beneficial parasitoid population.

While detection of the invasive Asian chestnut gall wasp in Michigan is not good news, practical and cost-effective management tactics can be used to prevent severe damage. Scouting to assess the abundance of current and previous galls can help identify where Asian chestnut gall wasp densities are relatively high. Monitoring yield is important to evaluate Asian chestnut gall wasp effects on nut production. The T. sinensis parasitoid seems to be spreading with Asian chestnut gall wasp and appears likely to play a major role in regulating Asian chestnut gall wasp populations in the long term.

It will be important to apply insecticide cover sprays only when necessary and to time sprays correctly to avoid affecting the beneficial parasitoid population. When expanding an orchard and planting new trees, consider chestnut cultivars that offer some resistance to Asian chestnut gall wasp . Integrating these options should help minimize impacts of Asian chestnut gall wasp and protect the Michigan chestnut industry over the long term.

Japanese beetle emergence has been reported in southern Michigan. Japanese beetle adults are considered a generalist pest and affect many crops found on or near grassy areas, particularly irrigated turf. Larvae prefer moist soil conditions and do not survive prolonged periods of drought. Adult Japanese beetle typically emerge around early July and feed on hundreds of different plant species. Adult beetles feed on the top surface of leaves skeletonizing the tissue. If populations are high, they can remove all of the green leaf material from the plants.

There are no established treatment thresholds or data on how much Japanese beetle damage a healthy chestnut tree can sustain, but consider that well-established and vigorous orchards will likely not require 100% protection. Younger orchards with limited leaf area will need to be managed more aggressively. Managing Japanese beetle can be a frustrating endeavor as they often re-infest from surrounding areas, especially during peak adult emergence in July. This re-infestation is often misinterpreted as an insecticide failure, but efficacy trials have shown that a number of insecticides remain effective treatment options.

Japanese beetle adults are a substantial insect and measure 3/8 to 1/2 inch long. The thorax is green and wingcovers are copper colored. There are five tufts of white hairs on both sides of the abdomen and a pair of tufts on the end of the abdomen that can help distinguish the Japanese beetle from other look-alike species. The legs and head are black.

Visual observation of adults or feeding damage is an effective scouting technique. Scout along a transect through orchards at least weekly until detection, paying special attention to the tops of trees. Because of their aggregating behavior, they tend to be found in larger groups and are typically relatively easy to spot. Pheromone and floral baited traps are available but are not recommended as visual observation is adequate to determine when beetles emerge and should be managed. For more information on insecticides available for the treatment of Japanese beetle refer to the current Chestnut Management Guide.

Moderate numbers of rose chafer are being observed around Michigan. Rose chafers are considered a generalist pest and affect many crops, particularly those found on or near sandy soils or grassy areas. The adult beetles feed heavily on foliage and blossom parts of numerous horticultural crops in Michigan and can cause significant damage to chestnut orchards. Rose chafers can be particularly damaging on young trees with limited leaf area. Rose chafers skeletonize the chestnut leaves but tend to consume larger pockets of tissue.

They are often found in mating pairs and fly during daylight hours. Visual observation while walking a transect is the best method for locating them. Because of their aggregating behavior, they tend to be found in larger groups and are typically relatively easy to spot. There are no established treatment thresholds or data on how much damage a healthy chestnut tree can sustain from rose chafer, but growers should consider that well-established and vigorous orchards will likely not require complete control. Younger orchards with limited leaf area will need to be managed more aggressively.

The rose chafer is a light tan beetle with a darker brown head and long legs and is about 12 millimeters long. There is one generation per year. Adults emerge from the ground during late May or June and live for three to four weeks. Females lay groups of eggs just below the surface in grassy areas of sandy, well-drained soils. The larvae (grubs) spend the winter underground, move up in the soil to feed on grass roots and then pupate in the spring. A few weeks later, they emerge from the soil and disperse by flight. Male beetles are attracted to females and congregate on plants to mate and feed. For more information on insecticides available for the treatment of rose chafer refer to the 2021 MSU Chestnut Management Guide.

Lecanium scale are being reported in high numbers in parts of southwest Michigan and may be present in other locations. Lecanium scale is a soft scale pest that attaches to and feeds on many deciduous plants in Michigan, most notably hardwood trees. Lecanium scale populations can build to extremely high levels over a series of favorable years before crashing due to natural enemies and disease. When present in low numbers, lecanium scale are often overlooked and are of little economic or aesthetic significance.

Growers need to check chestnut branches for evidence of this pest. Scales may look a lot like leaf scars or bud scales, so a close inspection is important. Some infestations have only a few scales per branch while others are well-covered. One tell-tale sign of scale activity is the shiny film of honeydew that the scales excrete onto surfaces beneath the scales. Increased ant activity is also associated with scale insects as they collect the honeydew.

The honeydew from scale can act as a substrate for sooty mold. On agricultural crops, sooty mold can become an issue when it ends up on the fruit or nut being produced. Additionally, the scales removes sap when feeding which can weaken shoots and even cause shoot death in some cases. Vigorous and healthy trees and plants can tolerate some scale infestation, but if high populations of Lecanium scale are found, control programs should be considered, particularly on small trees. Ideal control windows occur in early spring when buds are dormant and again in July when scale crawlers hatch. For more information on lecanium scale management, refer to the MSU Extension article, “Lecanium scale numbers building on chestnut.”

Potato leafhopper feeding damage is visible in some orchards. Like many plants, chestnuts are sensitive to the saliva of potato leafhopper, which is injected by the insect while feeding. Damage to leaf tissue can cause reduced photosynthesis which can impact production and quality and damage the tree. Most injury occurs on new tissue on shoot terminals with potato leafhopper feeding near the edges of the leaves using piercing-sucking mouthparts. Symptoms of feeding appear as whitish dots arranged in triangular shapes near the edges. Heavily damaged leaves are cupped with necrotic and chlorotic edges and eventually abscise from the tree. Severely infested shoots produce small, bunched leaves with reduced photosynthetic capacity.

Adult leafhoppers are pale to bright green and about 1/8 inch long. Adults are easily noticeable, jumping, flying or running when agitated. The nymphs (immature leafhoppers) are pale green and have no wings but are very similar in form to the adults. Potato leafhopper move in all directions when disturbed, unlike some leafhoppers which have a distinct pattern of movement. The potato leafhopper can’t survive Michigan’s winter and survives in the Gulf States until adults migrate north in the spring on storm systems.

Scouting should be performed weekly as soon as leaf tissue is present to ensure detection early and prevent injury. More frequent spot checks should be done following rain storms which carry the first populations north. For every acre of orchard, select five trees to examine and inspect the leaves on three shoots per tree (a total of 15 shoots per acre). The easiest way to observe potato leafhopper is by flipping the shoots or leaves over and looking for adults and nymphs on the underside of leaves. Pay special attention to succulent new leaves on the terminals of branches. For more information on insecticides available for the treatment of potato leafhopper refer to the current Chestnut Management Guide.

Black stem borer, also known as ambrosia beetle, is a substantial pest of young orchards. Female beetles bore into small diameter trees and create chambers to lay their eggs. They also infect these chambers with a fungus that will feed their larvae. Boring damages young trees and can cause outright tree mortality. Borer emergence seems to be winding down this season but has been observed in previous years through mid-July. Trapping is the only way to be confident in the presence or absence of black stem borer at your farm. Emergence typically begins in early April, peaks in late May and tapers off by the end of June. Growers with young trees (commonly less than 2.5 inches in diameter but up to 4 inches) should be actively trapping for and managing against damage from this pest.

Refer to the MSU Extension article, “Black stem borer: An opportunistic pest of young fruit trees under stress,” for more information on biology, monitoring and management.

Diseases

Existing chestnut blight infections (caused by Cryphonectria parasitica) can be observed at this time. To learn more about chestnut blight, visit the Pest Management section of the MSU Extension Chestnut website.

Weeds

Grassy weeds are particularly prevalent this season. Weed control looks very good in treated orchards. Most chestnut growers apply directed glyphosate applications in a band down the tree row to eliminate competition for nutrients and water. Glyphosate should be applied carefully to ensure it does not contact any part of the tree when applied.

Become a licensed pesticide applicator

All growers utilizing pesticide can benefit from getting their license, even if not legally required. Understanding pesticides and the associated regulations can help growers protect themselves, others, and the environment. Michigan Pesticide Applicator Licenses are administered by the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development. You can read all about the process by visiting the Pesticide FAQ webpage. Michigan State University offers a number of resources to assist people pursuing their license, including an online study/continuing ed course and study manuals. For more information on becoming licensed, contact Lisa Graves at 517-284-5653.

Stay connected

For more information on chestnut production, visit MSU Extension Chestnuts and sign up to receive our newsletter. Also, join us for the 2021 Chestnut Chat Series every Wednesday at 12 p.m. from May 5 through Sept. 8, 2021. This series of interactive Zoom meetings will allow easy communication between producers and MSU faculty. These informal weekly sessions will include crop and pest updates from Rob Sirrine and Erin Lizotte. In addition, MSU faculty will drop in to address timely issues and provide research project updates. Bring your field notes too! We want to hear what’s going on in your orchard.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under Agreement No. 2017-70006-27175. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

– Erin Lizotte and Rob Sirrine, Michigan State University Extension

Photo at top: Marigoule in northwest Michigan on June 30, 2021. Photo: Rob Sirrine/MSU Extension